“Rug pulls,” a notorious type of scam in the NFT world, now cost investors hundreds of millions of dollars a year. But it was only just this month when federal law enforcement officials bagged their first NFT “rug pull” suspects.

Two 20-year-olds, Ethan Nguyen and Andre Llacuna, face criminal charges in Manhattan federal court for allegedly scamming investors in their NFT project, Frosties. Nguyen and Llacuna purportedly collected $1.1 million from NFT buyers in January and then abandoned the project — in other words, pulled the rug out from under them. According to the government, the pair were plotting a second scheme right before they got caught.

Arrested last week, Nguyen and Llacuna are each charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering, and each face a maximum of 20 years in prison if proven guilty.

As interest around buying and selling NFTs has exploded, with the size of the market estimated at over $40 billion, bad actors have continued to pull scams on unsuspecting buyers. In the Web3 space, the term for the most common type of scam is “rug pull” — the founders of an NFT project pull the rug out from under its investors by disappearing with whatever funds they’ve amassed at the time. Chainalysis estimates that as much as $280 million was stolen from investors in rug pulls in 2021 alone.

Given their perceived anonymity, or at least pseudonymity, cryptocurrencies and their cousins NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, have long been considered by law enforcement to be havens for criminals. Recent cases, however, show that the government is getting better at catching wrongdoers in the space.

In February, Justice Department officials announced the seizure of $3.5 billion in cryptocurrency along with the arrest of 30-something husband and wife Illya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan in connection with allegations of laundering it. The Justice Department also revealed in January that it had appointed its first ever crypto enforcement team director, Eun Young Choi.

In the case of Nguyen and Llacuna, the FBI was able to demonstrate its newfound savvy at cracking strategies criminals employ to avoid detection and matching pseudonymous crypto wallets to the real-life identities of suspected fraudsters. Here’s how that played out, based on information from a criminal complaint filed by prosecutors.

Frostie, the No-Show Man

In recent months, a formula has begun to develop for successful NFT projects. Modeled on the success of profile-picture projects like Bored Ape Yacht Club, a project’s founders will create, or hire an artist to create, a base character and a collection of attributes. Those attributes are randomly distributed on a number of tokens, usually around 10,000, and the tokens are put up for sale with their art hidden. Interested buyers will “mint” a token, and sometime after the project’s tokens sell out, the art is revealed.

An example of a Frostie NFT, one of 8,888 similar but randomly-generated tokens.

This strategy went incredibly well for the Bored Apes — in order to buy one today, you’d have to cough up over $300,000, which is quite the sum considering the initial cost was around $200 in April, 2021. A similar strategy proved lucrative for Nguyen and Llacuna, who managed to sell their entire supply of 8,888 Frosties in under an hour, netting $1.1 million in Ether.

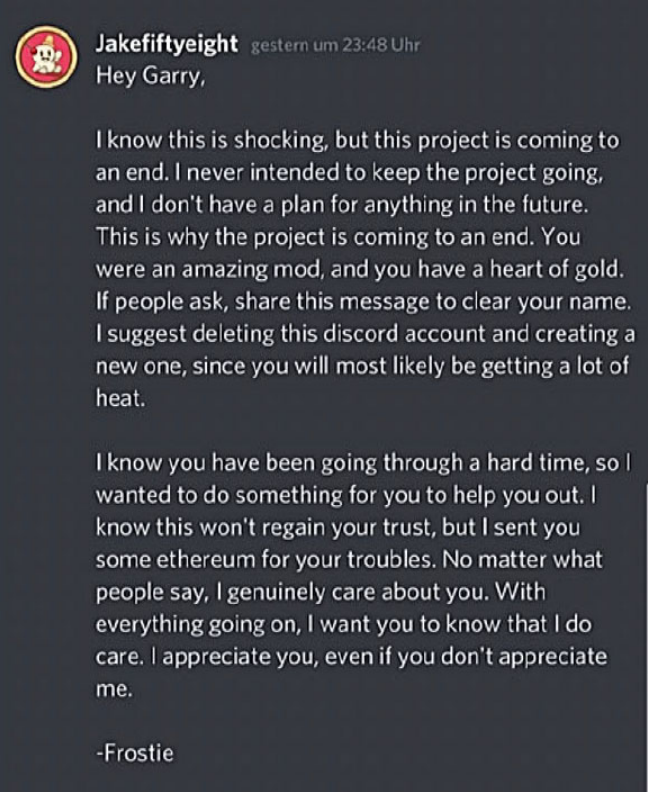

Unfortunately for their buyers, the founders had no intention of sticking around to deliver on the promises laid out in their roadmap, including building a metaverse, implementing staking and breeding features, and giving back to the community. A few hours after the sale, the founders shut down the project’s Discord server, website, and Twitter account, and even admitted to one of their Discord moderators that the whole project was a sham.

Nguyen, going by Frostie, appears to discuss what happened to the project on a Discord server.

Nguyen, going by Frostie, appears to discuss what happened to the project on a Discord server.

FBI identifies founders

Nguyen and Llacuna seemed confident that they had pulled off their scam, even going as far as to plan another one, according to the government. However, they committed a number of unforced errors that made it possible for the FBI to trace their online personas back to their real-life identities.

The alleged fraudsters’ main attempt to cover their tracks on the blockchain was using Tornado Cash, a cryptocurrency “mixer” or “tumbler” that makes it possible to transfer cryptocurrency from one wallet to another without creating obvious links between them. Someone inspecting the blockchain would just see one wallet depositing crypto into the Tornado protocol, with no way of linking it to the wallet that eventually receives the funds.

The co-founder of Tornado Cash, Roman Semenov, has claimed that the tool is important for securing the privacy of anyone involved in crypto, and isn’t just an easy way for money launderers to get off scot-free. Furthermore, he claims that he doesn’t even have the ability to spy on the identities of contributors, since the tool operates autonomously on the blockchain.

Nguyen and Llacuna allegedly transferred the equivalent of $678,000 in three separate transactions from the wallet where the Frosties' profits were stored to Tornado Cash, successfully obscuring their trail on the blockchain. The FBI would have to turn to Web2 companies in order to uncover the identities of the alleged fraudsters.

Their simplest tool? A grand-jury subpoena. Over the course of the investigation, the FBI subpoenaed Discord, Coinbase, Metamask, Citibank, OpenSea, GoDaddy, T- Mobile, Charter Communications, Bitpay, Fiverr, and PayPal.

Of likely interest was information surrounding the IP addresses used to access the accounts associated with the projects. According to the complaint, Nguyen was identified after the same IP that accessed his Discord account was used to conduct business on a Coinbase account registered to him. Llacuna was identified after the phone number and email address he registered in his Discord was linked to a Coinbase account registered to him.

Once the authorities had these links, they were able to uncover other corroborating evidence. Nguyen used a Citibank credit card to register the Frosties website, buy a VPN in an attempt to mask his IP address, and pay for a freelance artist on Fiverr to design the art for the project and the website. Llacuna accessed his Discord account, under the username “heyandre,” from the same IP address used to access his Opensea account, which included his email address and an ENS registration for the “cryptoandre.eth” domain.

As described by the government, the affair goes to show that while it’s possible for a criminal to obscure their trail on the blockchain, any interactions with banks or exchanges can lead back to a real identity, as they often have anti-fraud Know-Your-Consumer (KYC) requirements. It’s probably not a great idea to register illicit accounts under the same email address, either, especially if the email address contains part of your name, as both Nguyen’s and Llacuna’s purportedly did.

Rugging the rug pullers

The FBI also found that an email linked to Nguyen was used to create the OpenSea account for another crypto project, Embers NFT, which bills itself as “A community driven NFT project made up of 5,555 animated Embers living in the core of the blockchain.” An IP address linked to Llacuna was used to make a $50,000 donation to the Red Cross Foundation, a promise made by the Embers project.

Similarly to Frosties, the founders of the Embers project were only referred to pseudonymously — if that sets off your alarm bells, you may be surprised that the founders of the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s parent company, Yuga Labs, remained pseudonymous until recently. Therefore, none of its potential buyers could link the project back to the alleged Frosties scam.

When the news of the arrest of the founders broke, most members were blindsided, though the news took some time to set in. Ten minutes after the first warning was posted, users were still wishing each other well, and exclaiming “WAGMI!” (“We’re all gonna make it”).

News of the fraud charges had a muted impact in the NFT community at first.

News of the fraud charges had a muted impact in the NFT community at first.

Though some users caught on right away, many others continued chatting innocuously; the project, like many other recent NFT projects, rewards active users with presale access to the collection through a spot on a “whitelist” or “allowlist,” making it easier for them to purchase an NFT from a collection with high demand. Though the fraud was revealed before the Embers sale was scheduled to go live, many members lamented that they wasted their time trying to earn a spot on the whitelist by chatting, creating fan art, and getting others to join the Discord server.

Community moderators have said they weren’t in on the scam — one mod, who goes by Tikwizz, sent approximately 9,000 messages on the Discord server in the past month, and claims to have been only paid .1 eth, around $312, for his efforts, with the promise of another .1 eth after the public sale.

This scam, though narrowly averted, will likely be a hot topic in the crypto community, especially as users question the legitimacy of projects they’ve invested time and money into. At the very least, it serves as a reminder that the pseudonymity crypto has embraced doesn’t come without risks.